Beryllium, Criticality, and the Periodic Table of Death & Mystery Part 1

I despaired in finding anything to write about beryllium (Be), and then I saw Oppenheimer (2023). It is a seriously great “middlebrow” (4) movie and I highly recommend it. It also exposed an embarrassing hole in my education of what was probably one of the most profound discoveries in the history of humans*—unlocking the nuclear power of the elements that reside in the Periodic Table. Not only that, but I live in New Mexico, and I have never visited the Trinity Site (only 150 m/250 km from my house) or truly understood what Los Alamos meant, even though I once worked in a lab with a scientist (1) who was part of the Manhattan Project and who signed the Szilárd petition (2).

Understanding Criticality

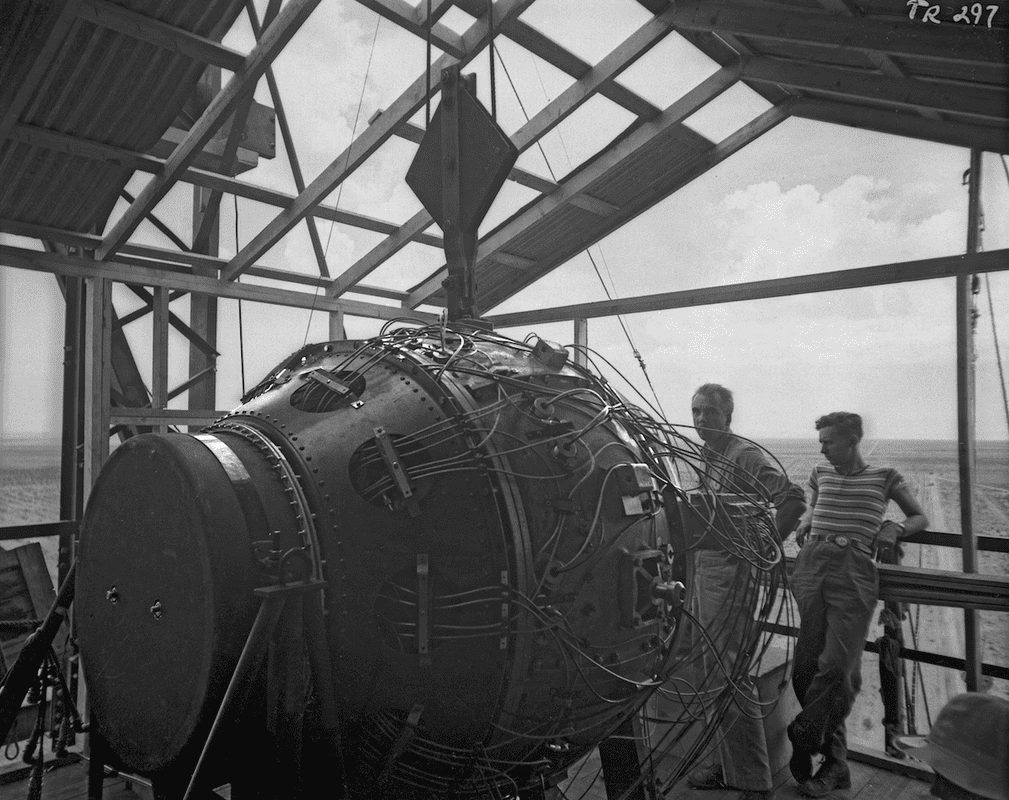

A little atomic bomb history before we get to beryllium. In the early 1940s, two different elements were used to create the cylindrical (5) or spherical pit cores (6) of four fissile (7) nuclear weapons during the Manhattan Project, three (3) of which were detonated during World War Two: The Trinity Site bomb core (nicknamed Gadget) was of plutonium (Pu) mixed with gallium (Ga) for stability, as was the Fat Man bomb dropped over Nagasaki, Japan. The core of Little Boy, which was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, was made up of uranium (U). Because of enrichment issues, more U was needed for the detonation (64 kg/141 lbs.) than Pu(6.2 kg/13.66 lbs.). The amount necessary for a sustainable fissile detonation was linked to something called criticality (10). It’s sort of a measurement of how close or far away fissile material is to detonation and depends on factors like amount of material, density, shape, and neutron reflectors (12).

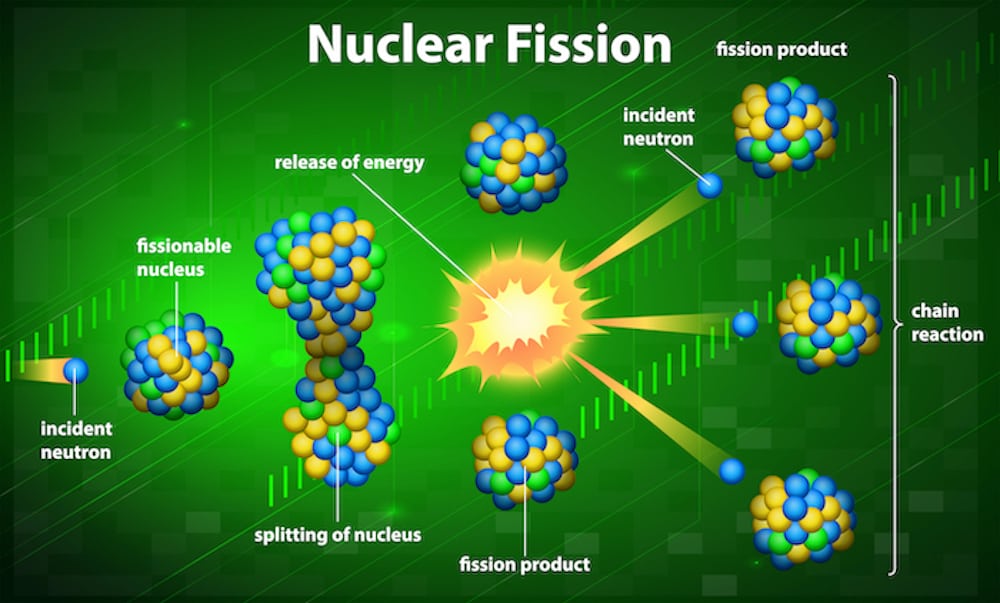

Fissile materials (11) are those that split apart after incorporating a neutron and are capable of sustaining a nuclear reaction. A neutron is a neutrally charged particle that is a part of the nucleus of every element in the periodic table except hydrogen (H) (8). Each of these fissions or splits releases smaller elements, more neutrons, radiation, and energy that can be felt as heat. But not all the neutrons released by the atomic splits are incorporated in other molecules—in this case Pu or U. Some are lost into the space surrounding the core. THIS IS KEY: So long as the incorporation of the neutrons and the number of splits is kept below a certain level (neutrons “lost” > neutrons released by fission/split reactions), the core material is considered subcritical for a chain reaction event and detonation.

However, once the rate of neutrons released by fission reactions become GREATER than neutrons lost to the surroundings, the core becomes supercritical, and a chain reaction of neutron incorporation, fission, radiation, and energy release starts the detonation (10). The 6.2 kg Pu/Ga core of Fat Boy exploded with the force of 21 kilotons of TNT. That’s 21 thousand tons or 42 million lbs. I honestly can’t even comprehend what that means.

I mentioned that four atomic cores were created for the Manhattan Project, but only three were detonated. It’s the fourth one that I will link to beryllium. Nicknamed Rufus, it was to be dropped over Tokyo if Japan refused to surrender after Nagasaki. The Japanese surrendered, and the Rufus Pu/Ga core was moved back into the realm of research at Los Alamos. There, in short order, it acquired a new name: The Demon Core. Why? Because two of the scientists who used it to examine criticality would end up dead, one of them due to his fatal mistake wielding a screwdriver and a simple beryllium tamper.

Beryllium, the Demon Core, and the Periodic Table of Death and Mystery Part 2

In part one of the beryllium (Be) story, you learned that four atomic cores were created for the Manhattan Project, but only three were detonated. The fourth atomic bomb, made up of Plutonium and Gallium (Pu/Ga) and originally nicknamed Rufus, was moved back to Los Alamos, New Mexico, for further research. In short order, it acquired a new name—the Demon Core—when two scientists who used it to examine criticality would end up dead. The scientist linked to Be, Louis Slotin, exhibited a reckless carelessness that could have wiped out Los Alamos and its surrounds from an atomic explosion. Carelessness he rectified by sacrificing himself.

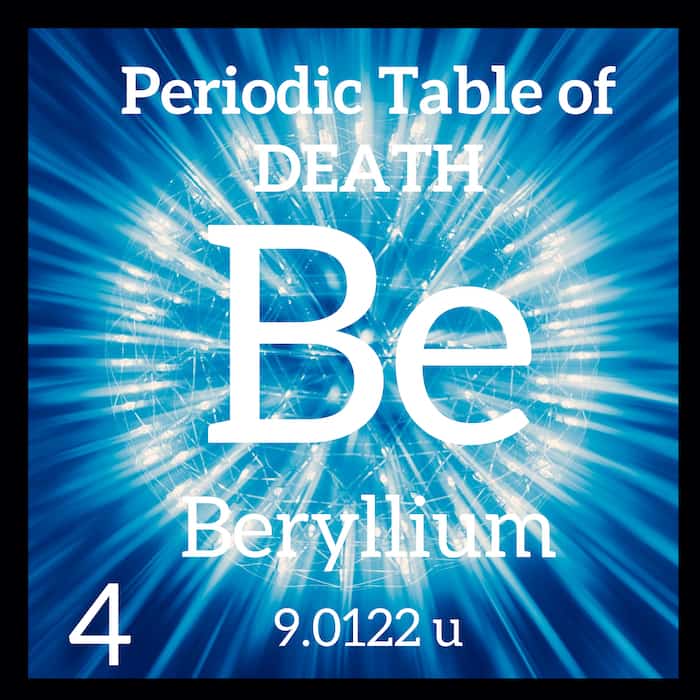

But first, a little about beryllium. With the atomic number 4, it’s the fourth element of the periodic table, group 2, period 2. In pure form, it’s a lightweight, brittle silvery metal with a high melting point (2468°C, 4474°F). Be tastes sweet if licked, which is kind of a weird property, and its discoverer, Nicholas Louis Vauquelin (1763-1829)(1), originally wanted to name it glaucinium (glykys is Greek for sweet) (2). Instead, it was named for the gemstone, beryl, which contains Be. Now that you know Be tastes sweet, you might be curious to lick it yourself. Don’t. Be is toxic to humans in pure form if ingested or inhaled.

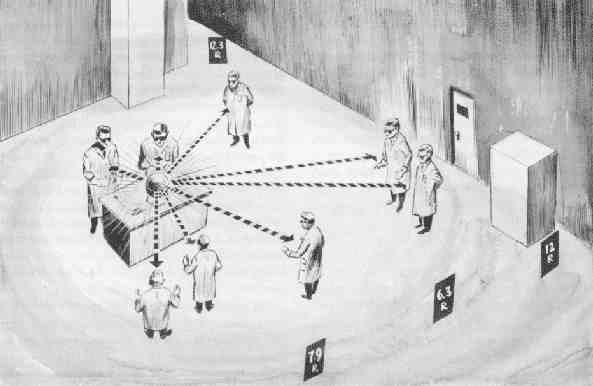

In criticality research on the atomic bomb cores, Be was used to create tampers—half dome-shaped bowls similar to those metal cloches (3) that cover room-service food at fancy hotels. The tamper’s Be composition was very important because the element Be reflected neutrons back into the Pu/Ga core. They were used experimentally to assess the core’s neutron multiplication rate. The caveat? If the core ever became completely surrounded by the Be tampers, too many neutrons would be reflected back, start a super-critical chain-reaction, and—nuclear detonation. A gap was left between the two encasing tampers so some of the neutrons could escape.

During criticality experiments, the bottom half of the spherical Pu/Ga core was nestled inside the first tamper. The second tamper was used to cover the top half of the core and manually controlled by the scientist conducting experiments. You heard that right. Manually controlled. The scientist raised and lowered the top Be tamper using a thumb hole. To maintain a gap for neutron escape, protocols dictated shims be placed between the two Be tampers such that the core was NEVER completely covered (4).

Louis Slotin ignored protocol. Instead of shims, he used a flat-head screwdriver to control the size of the gap between the two tampers. He was known to be a bit of a show-off and photos of him at Los Alamos saw him dressed in blue jeans, cowboy boots, and aviator shades. The Cool Physicist. He was adept at “tickling the Dragon’s Tail” which these criticality experiments had been labeled because they were extremely dangerous (5).

Slotin and seven other lab personnel, from technicians, to scientists, to a military guard, were present on May 21, 1946. Slotin was demonstrating his method of measuring criticality using the Be tamper and his screwdriver. This time, the screwdriver slipped. The Be tamper slammed down completely covering the core. Instantly, the room filled with a blinding flash of blue light and a wave of burning heat. The core turned supercritical, releasing a burst of radiation. Nuclear explosion was imminent. With a twist of his wrist, Slotin flipped the Be tamper to the floor and stopped the chain-reaction build up and blast. But it was too late for Slotin. His position over the supercritical core shielded the other men in the room but caused him to receive a lethal dose of radiation. He died of acute radiation poisoning nine days later.

You know what the saddest part was? Louis Slotin was leaving Los Alamos for a teaching position at the University of Chicago. His last interaction with the Demon Core was a training demonstration for his replacement. Knowing he would die, Louis called his parents who were flown to his side to be with him in his final hours.

After Louis Slotin’s death, Los Alamos ended hands-on work with the nuclear bomb cores.

*I would place the discovery of DNA right up there, too. Oh. And fire.

As always, these are my own opinions based on my biases, knowledge, and understanding, and the websites I’ve linked are in no way an endorsement.

I went ahead and embedded the references in the articles instead of adding them in a list at the end. I learned A LOT from these posts about something sorely lacking from my education. This research also inspired me to write a novella with a heroine who worked at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project and lived near Roswell during the Roswell incident. Here’s a nice bonus cover from that story tentatively titled, Canyon Lies and Starlit Skies.

Aluminum, Sapphire Glass, and the Periodic Table of DEATH & Mystery

Aluminum, Sapphire Glass, and the Periodic Table of DEATH & Mystery

Leave a Reply